Boxes of railroad ties looks impressive, but does little to run a railroad. Establishing the track locations and glueing the ties is the middle step for me in building track. The tutorial below reflects the method I've developed over the years. It is not necessarily the best way, or even the correct way. But it works for me. Your results may vary.

Establishing the track centerlines is an exploratory process, going from what was drawn somewhat to scale on paper to what actually works in 3-D. Many times the trackplan changes a bit at this stage as visual composition of the scenes emerges. Industries get moved around due to clearance point constriction, scenic features are added or deleted as the space dictates, and operational considerations now become evident.

To establish track centerlines I use 3/8" splines ripped from the clearest, knot-free 2x4's I can find. The longer the better. I can usually find the one or two such pieces I need for this in the 14' bin at the lumber yard. The importance of having a knot-free spline is that it will bend evenly over its length, and of course, won't snap in two when bent. I can usually bend a 3/8" spline down to 54" radius without breakage. Wetting the splines in advance allows much tighter radii, and ensures against them breaking.

Transition spirals, curvature easements, etc. all happen naturally with this method as the wood bends into the required arc and then back to tangent (straight). No fancy calculations needed. It's like cheating! But why not, it's easier than a 4 year degree in civil engineering.

What follows below is for establishing trackcenterlines on a flat surface. The splines can also be used when the benchwork is an open grid. This process will be described later on the Spline Roadbed section.

Begin by laying out approximate track locations with the splines. I usually start with the mainline, then to passing sidings, then to spurs. Flathead common nails are driven into the homasote or micore subroadbed far enough to hold the spline in position. Spring clamps hold the splines together where turnouts ocurr. I generally don't worry about what the turnout frog number is, as long as it's appropriate for the location. Frog numbers are essentially undefined- being, for example a #9.27 when measured after completion. And using this method produces a lot of flowing, curved turnouts- and trackwork in general. If a turnout with a true, straight route is desired, clamp a 2' level to the spline along the straight route and then arc a diverging route/spline from it.

Here is where things get interesting as scenery and structure locations transition from paper and pencil drawings to 3-D. And this is where a lot of rethinking takes place. Many nails get pulled, splines shifted, and ......hmmmm, maybe it needs to go like this...

To establish a radius arc I use a camera tripod with a spline as the swing arm and pencil through a drilled hole for marking the arc. Here you can see the pencil of the tripod arm hovering over the spline, rechecking the true radius. (oopsie on the photo. Forgot to set "white balance". My bad.)

To enable a transition spiral, or easement, into and out of the established radius, define both ends of the curve as being a couple inches broader than the actual radius arc would produce. These become your tangent points into and out of the curve. Then pull the middle of the spline inward to follow the actual drawn radius of the swing arm. Presto. A transition spiral!

As the centerlines are finally established, and all is correct,....hopefully, draw a line along the base of the spline. I generally establish the aisleside of the spline as my true centerlline. This avoids confusion given the 3/8" offset of the spline thickness.

I like having, or at least starting with, a very straight tie edge. To do this I use the splines again, but now as an alignment tool. Accurately cut, 8' ties (2" in O scale) are marked dead center (1"). These are laid on the marked track centerline and a spline is butted up against the tie edge. Nails again hold the spline in place. I work my way along, nailing a single spline over the length for a given track. I glue all the ties along one spline length and remove it, then reset it for another set of ties.

It generally works better starting at the furthest distance from the aisle and working toward the front. And I usually make the aisle-side edge be the spline edge for the ties.

To define where tie lengths transition from normal 8' ties to the longer, switch-length ties, I lay two center-marked ties on the track lines and slide them along the main and diverging routes until the ends are butted. A full length tie is then placed at that location. Switch length ties are then used from that location back to the switchpoint end of the turnout.

I will cut 3 or 4 intermediate lengths of ties for switches. After the rails are down, I go back with a cut-off disc and trim the ties on the diverging route to the typical graduated, prototypical look. Yup, this is cheating, but when completed and the ends stained, no one's the wiser. And best of all, the ties look like they were carefully cut just for this particular turnout.

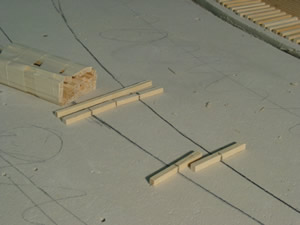

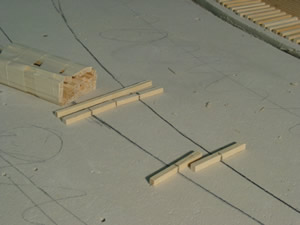

Here a spline has been positioned at the diverging end of a turnout and is ready for tie-glueing.

What about having the mainline be higher than the adjacent trackage on a flat surface such as this? How is that done? Two methods work.

a) glueing a notched-on-each-side tie flat (see Cutting Ties section) along the centerline of the mainline and then sanding/beveling it down to adjacenct trackage. The dual notching allows the flat to bend with track curvature. Ties are then glued to this flat. Or-

b) after the process of THIS tutorial is completed, use a utility knife to cut the subroadbed along each mainline tie edge, gently lift the subroadbed, and slide "tie flat" or other shim material under it. Thus the mainline is raised a bit relative to the surrounding trackage and the transition between the two is done smoothly by the subroadbed. Doing this AFTER the ties have been sanded ensures a constant flow of tie height through the transition.

I use Titebond yellow glue. I'll run a bead of glue about 18" and spread with a stick, intentionally leaving a gap on the spline-side. One end of the tie is placed in the glue and then slid through the glue and up against the spline. This keeps the minimum amount of glue from getting on the spline.

If you've cut your own ties as described on the "Cutting Ties" section, there will be some ties with knots material in them. Toss those aside as they will not sand evenly later on.

The distance between ties, and their alignment can be varied depending on whether the track is main line, siding, or little used industrial.

As soon as the spline length of ties is completed, remove the spline. Yellow glue sets up quickly. Letting the spline sit overnight with freshly glued ties up against it is NOT a good idea.

It is best to pull the nails on the OUTSIDE (non-tie side) of the spline first. This allows the spline to fall away from the ties rather than springing back into them, distrubing their position.

If you wish to have a more staggered edge to the line of ties, now is when you can nudge of the ties right or left to create this effect.

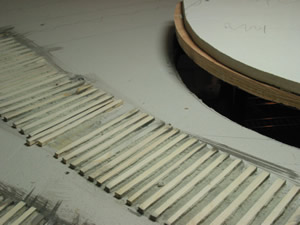

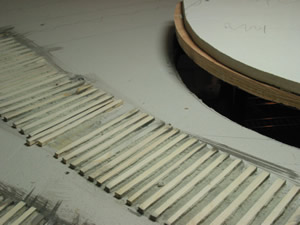

A completed section of ties. I did the ties on the right first, removed the spline, and then reset it for the left and its ties.

Next I wipe a quick coat of tie stain across the top of the ties. I make my stain from a mixture of chocolate brown and black latex paint, diluted about 2/3 with water. Experiment with the amount of brown to black proportions and water mixture until you like what you get.

A belt sander with #80 grit (O scale) belt is next. I work VERY lightly across the tops of the ties to start. The higher ties will quickly show themselves. As they are brought down to the overall tie height more downward pressure is applied.

The sander can make quick work of the white pine (or basswood of comercial ties) so keeping track, so to speak, of tie height in the midst of the sawdust is important.

If you are using commercial, "Low Profile" basswood ties, I'd suggest a much finer grit paper- assuming you're planning to sand at all.

Here the higher ties have been reduced and I'm getting closer to a uniform tie height. It is important to keep the sander level as you along lest the ties become rounded on their ends, or the entire section is at a bevel (an undesirable form of super-elevation).

No matter how careful I am with the sander, a few ties will get dislodged. These ties are placed in between two adjacent ties and sanding continues. This will bring the currently loose ties to the same height as their neighbors.

I use a straight edge to frequently check for vertical curves as I sand. It is common to have subtle waves form as you sand. Working slowly and frequent checking prevents this.

As I slide the straight edge along, high spots will show themselves by a rocking motion of the straight edge. The sander is placed on the high spot and brought down to level, feathering out from this spot in each direction.

Sanding the wider switch ties involves moving the sander side to side as one would a clothes iron pressing a shirt. (Thanks for the pre-college laundry tutorial mom!)

Once the ties are a uniform height, the area is vacuumed. Remember to set the loose ties aside or you'll be digging into the bowels of the Shop-Vac (ahem.) Now those few previously dislodged ties can be reglued back into their original position and their height checked with the straight edge.

Note that a few ties have just barely been reached by the sanding belt. If there are no high spots, this is a good time to stop.

If you are wanting to create uneven, poorly maintained industrial trackage, the sander is only too happy to oblige. Experiment. NOTE: This works better in O scale where the mass of the equipment keeps things on the rails.

The pencil is pointing to the ragged burrs on the ties left from the sanding. I use a wire brush to clean these off with a fast scrubbing motion and revacuum. This is a quick process.

If desiring a very detailed tie (in O scale) I have next used a house paint-scraping wire brush to scribe tie/wood grain into the tie. This is only worth doing if the area is up close and subject to macro photography. You will observe that the 80 grit sandpaper tends to create some grain on the ties.

Finally it's time to stain the ties. I begin with a wash of water over the ties, soaking them, and letting the water sit for a couple minutes. This prevents the dry ties from absorbing the color of the stain too quickly.

Then the stain is applied to this sloppy mixture. I add enough stain to color the tie, yet allow some of the wood color to show through. As the ties dry, more water and stain can be added to achieve the desired look for a given location. You can always add color, but not remove it without resanding when dry.

This process goes quickly, and is a bit of an artsy step with the ties being a canvas on which you're creating your Van Gough.

On track with little traffic (spurs, etc.) I will sometimes make the stain lighter, and even do a dry brush of gray to simulate sun-bleached and silvered, weathered ties.

Once dry it's time to spike some rail.